Daggett

For those that enjoy rich and intriguing Mojave Desert history, Daggett is a must-see stop. Located eight miles east of Barstow and eleven miles west of Newberry Springs, the town is easy to access if you’re near either place or traveling down I-15 or I-40. From I-15, exit on Ghost Town Road (exit #191) and head south, or from I-40, take the Daggett exit (exit #7) and head north. Plan on spending an hour or more to visit the various sites discussed in this article.

Written by Cliff Bandringa & John Wease

Calico & Silver – Borate & Borax

Silver was discovered in the nearby Calico Mountains in 1880 and, soon afterwards, so were large deposits of borax. By 1882, the nearby town of Calico became a booming town. About the same time, the Southern Pacific Railroad built tracks to what became known as Calico Junction to ship in miners and supplies and ship out silver and borax. Soon after that, Calico Junction was renamed to Dagget in honor of then Lieutenant Governor John Daggett, who also owned a mine in Calico.

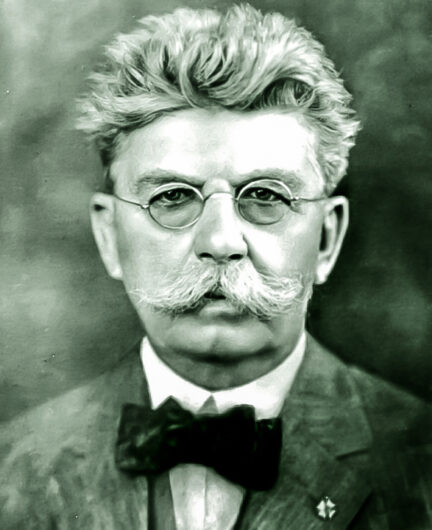

In 1891, Pacific Borax Company, led by Francis Marion Smith, known as the “Borax King”, moved down from Death Valley and established a mine and town named Borate inside the Calico Mountains. Using the same famous 20 mule teams used in Death Valley, Smith shipped borax ore to Daggett to be shipped out on the Southern Pacific (soon to become the Santa Fe). Later, wagons for the 20 mule teams were built in Daggett. One still exists in town today.

For the next 25 years, Daggett became the supply center for not just the silver and borax mines, but many other area mines. Even mines to the north were involved, including those in distant and remote areas such as Death Valley, some 200 miles away. At times, monthly shipments of silver out of Daggett averaged $100,000. Some seven to eight freight cars, each with fifteen tons of borax, shipped from Daggett each day.

Narrow Gauge Railroads

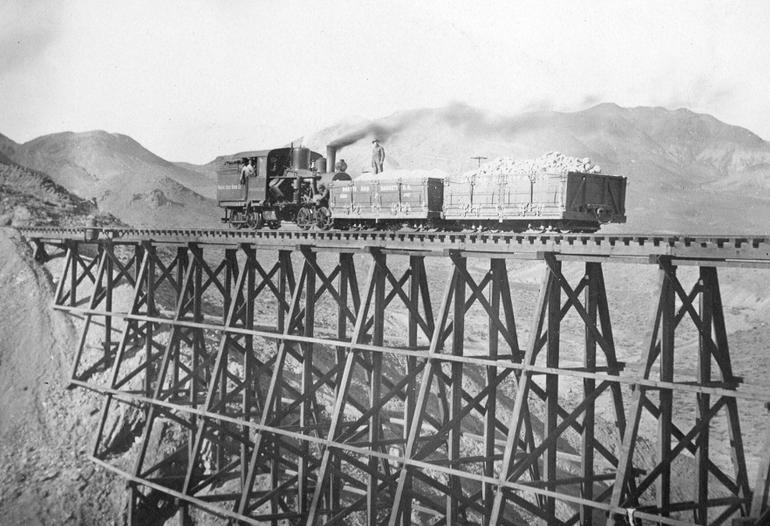

In the early 1890s, two narrow-gauge railroads were built, one from Calico to Daggett, and the other from Borate to Daggett. They replaced the mule teams and increased the amount of ore shipped to Daggett and beyond.

The railroad to Calico was called the Daggett-Calico Railroad. It started running in 1888. It hauled ore to the Ore Grande Milling Company that was located across the Mojave River from Daggett. You can still spot its foundations on the side of Elephant Mountain west of Daggett-Yermo Road today.

Smith built his Borate and Daggett Railroad in 1898. A few impressive trestles were built to span a few canyons. The foundations of those trestles can still be seen in the Calico Mountains today. The cost of shipping borax was lowered from $2 per ton using the 20 mule team, to $0.12 per ton using the Borate and Daggett. Later, this railroad would inspire Smith to build the famous Tonopah and Tidewater Railroad, then later still, various commuter railroads in the San Francisco Bay Area. The Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) now utilizes some of the rights-of-ways originally established by Smith’s railroad.

Santa Fe Railroad

In 1888, the Santa Fe Railroad wanted to build a large rail facility and locomotive shop near Daggett. This news got out to the people of Daggett and when Santa Fe attempted to purchase plots of land outside of town, the prices of land suddenly went up. Not wanting to pay the high costs, Santa Fe looked six miles to the west to a place called Waterman Junction. Here, they purchased enough land to build their facilities, where they still stand today. Waterman Junction was renamed to Barstow in honor of William Barstow Strong, President of the Santa Fe Railroad.

Daggett missed out on this potential economic boom of the railroad setting up operations in town. Instead, it was the beginning of several economic blows to the town over the next ten years.

Boomtowns turn to Bust

In 1896, silver prices fell to sixty-five cents per ounce. Because of this, most of the Calico silver mines closed and the miners moved on to the next boomtown. Pacific Coast Borax continued its large-scale mining operation until 1907, when Smith decided to move his operation back to Death Valley after finding several larger deposits of borax there.

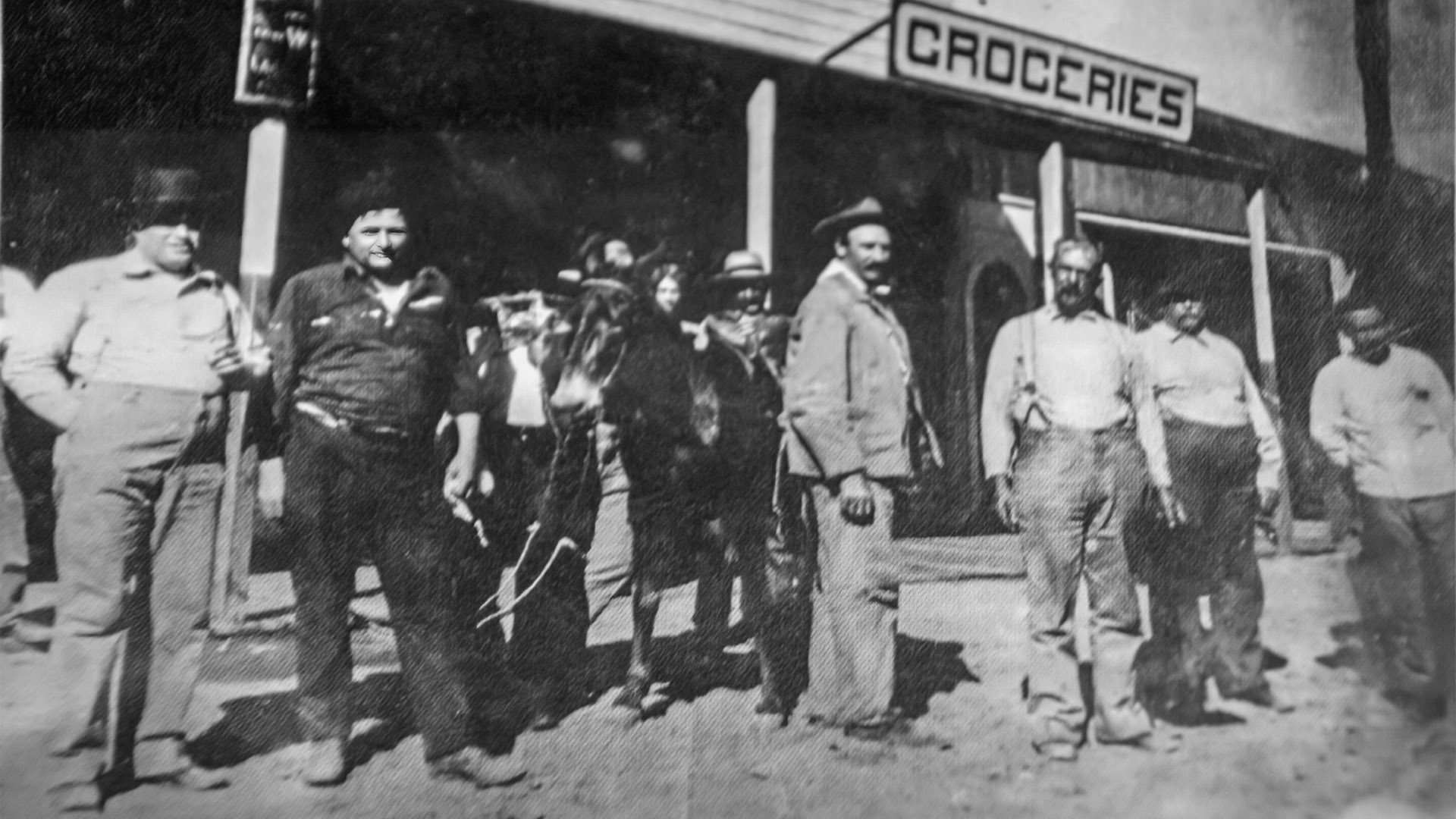

Around 1900, the gold and silver mining boom began in areas around Death Valley. Daggett became the jumping-off point and supply town for these remote places over 200 miles (320 km) to the north that could only be reached by foot, mule or sometimes wagon. Many people got off the train in Daggett, stayed at the Stone Hotel (built in 1875), got their supplies, and headed north. Famed prospector Walter “Death Valley Scotty” Scott stayed at the Stone Hotel often and was a regular around Daggett (as seen in one of the pictures) as he promoted his “vast mining interests” around Death Valley.

A year later, in 1908, a fire destroyed much of Daggett’s business district. The fire burnt off the second floor of the Stone Hotel, but its ground floor still stands today. With the mines now closed, there was no money and little incentive to rebuild. Daggett could easily have become another forgotten ghost town, but the people of Daggett kept it alive.

Helen Muir

Famed American naturalist John Muir’s daughter, Helen Muir, was a longtime resident of Daggett. She contracted tuberculosis in 1905 and, following her doctor’s orders, moved to the desert for drier air. She first tried Arizona but settled on Daggett. For that reason, John Muir frequented Daggett while visiting his daughter. Helen remained in Daggett for about twenty years. She was responsible for classifying and documenting many of the desert plants we know today. In getting to various places in the desert to study plants, she hitched rides aboard freight trains and became well-known by train crewmen.

Daggett Ditch

With the mines and the local economy prospering in the 1890s, naturally there was a demand for water, not just culinary water but also for agriculture. Various companies were formed to build what is now known as the Daggett Ditch. It would extract water from the Mojave River, about two miles up-river where it narrows near the western end of Elephant Mountain. At the time, it was the largest irrigation project in the Mojave Desert.

In the Mojave River, water flows underground most of the time. Therefore, a normal dam couldn’t be built to divert the water into a canal. Instead, a “submerged dam” made of flat material was driven down through the sand of the riverbed to divert water up and out of the river. After several attempts, the concept worked and water flowed into the ditch we see today, past the town of Daggett (some was taken out for domestic use), and on to irrigate new farms east of town.

Around 1900, the ditch was concreted and covered to reduce water loss from seepage and evaporation. However, the unpredictable water of the Mojave River simply went under the submerged dam and less water was being diverted into the ditch. That, coupled with the economic decline of the mines closing, spelled the end of operations for the Daggett Ditch. The last company that operated it filed for bankruptcy and the ditch was abandoned. Today, you can still see the ditch on the north end of Daggett, where it stretches to the west between the shores of the Mojave River and the railroad tracks.

Road Building, National Old Trails Road and Route 66

As the automobile become more popular around 1910, a national movement began to build cross-country roads. One of the first was the National Old Trails Road, which would later become Route 66.

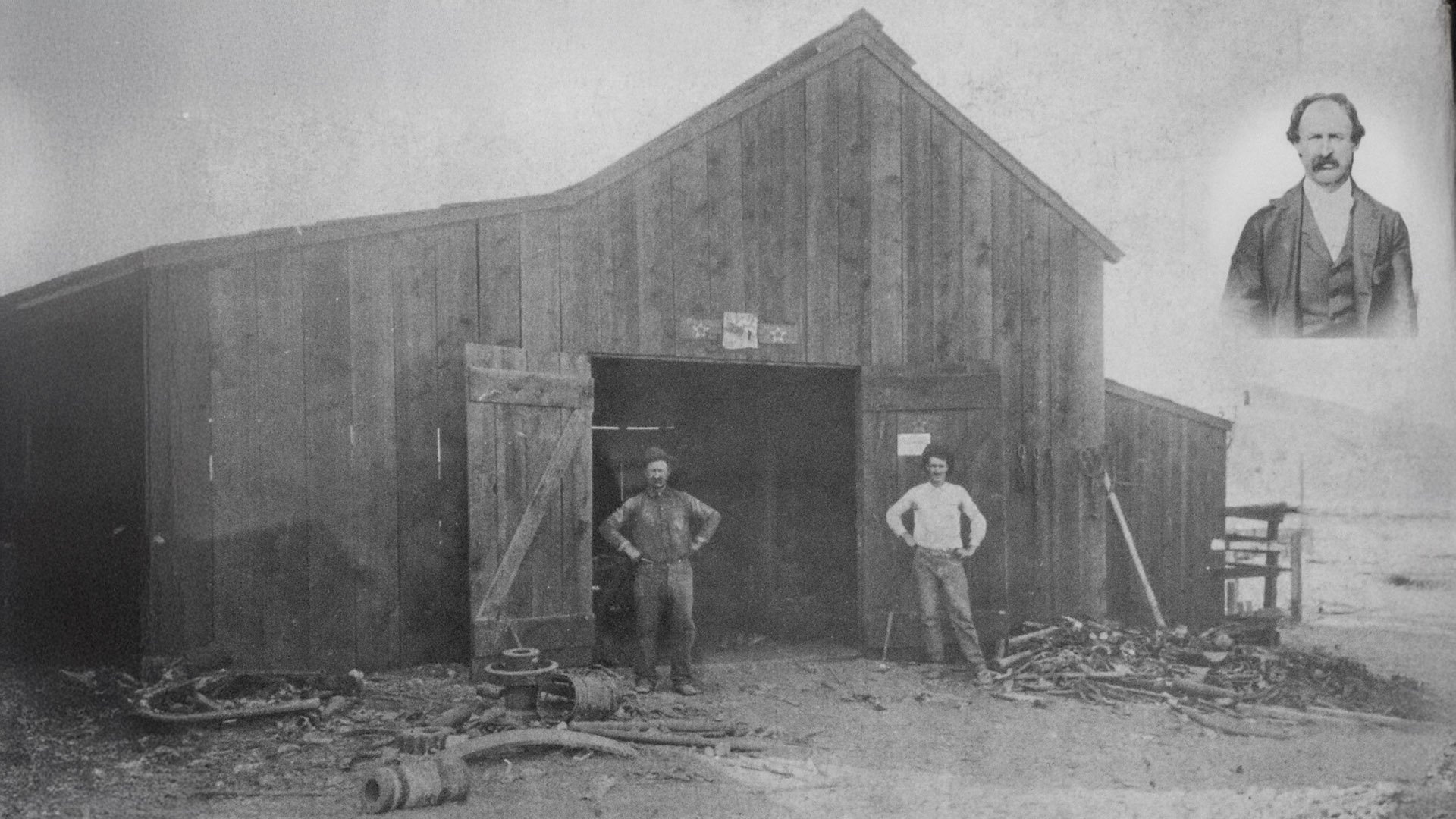

Seymour Alf moved to Daggett in 1885 and built a large blacksmith shop to serve the booming mining industry that was occurring then. He also began building wagons that were used on the ore hauling 20 mule teams. Alf also built equipment that was used to build and grade roads to all the mines.

When the government sanctioned a road to be built in the 1910s, Alf won the contract to grade the road from Barstow to the California/Arizona border. This would become part of the path for National Old Trails Road that stretched from Maryland to California.

When Route 66 was sanctioned in 1926, it used a portion of the same route as National Old Trails Road. Because of this, Alf was credited for trailblazing the path of Route 66 through this part of the Mojave Desert.

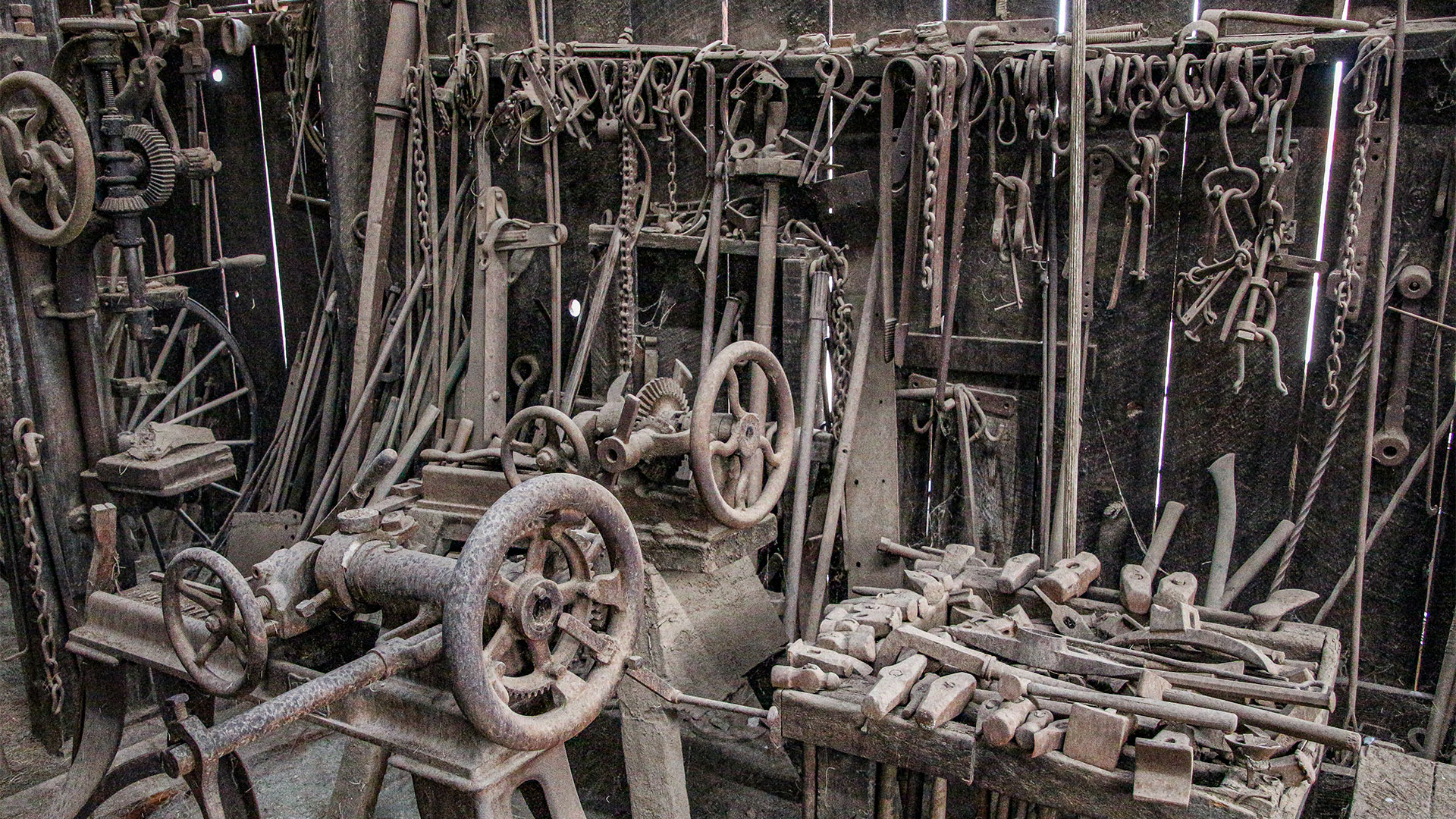

Alf’s blacksmith shop still exists in Daggett today. The horse-drawn road grader that was used to grade what is now Route 66 sits in a yard next to the shop. The tools that Mr. Alf and his crew used are still sitting in the shop, waiting for the next job to perform. Next to the shop, an original 20-mule team wagon, which was used during the boom years of Daggett, is safely parked inside a building, protected from the sun.

Daggett Today

As of a 2000 census, the population of Daggett is about 200. Many buildings from its heyday are gone but there is still a few buildings remaining. The old Stone Hotel from 1875 sits next to the classic Desert Market, built right after the devastating 1908 fire, on Santa Fe Street. The rusty-looking Daggett Garage, built in the 1880s, can’t be missed, as Santa Fe Street was paved around it. The Daggett Ditch can be found bordering the north edge of town.

Below is a street map of the small town that points out various places of interest. A great place to start is its small museum located at the Daggett Community Services District building. Check Google or their website at www.daggettcsd.org on when they’re open.