Newberry Springs History

This article provides a detailed explanation of the history of Newberry Springs, starting in the 1920s, along with accounts of what it was like living in this desert community from the 1940s until present.

Compiled by Cliff Bandringa, January 2025, from the writings of Bill Smith and John Wease

Bill Smith experienced living in Newberry Springs on and off for most of his life, starting in 1942. He got to know many people that had lived in the community beginning in the 1920s. His accounts written here are from what he learned from those people. After working in the Los Angeles area, Mr. Smith returned back the family homestead in Newberry Springs. Mr. Smith moved to Utah in 2018 where he lives today.

Keep in mind that the following text will refer to the town as Newberry Springs, even though up until 1967, it was referred to as just “Newberry”. It was in 1967 that an individual influenced the U.S. Postal Service to rename the community to Newberry Springs.

NOTE

About Page

Life Before World War 2 (1941)

Much of what would become Newberry Springs materialized between the years of 1880 and 1940. This included the arrival of the railroad, and later the arrival of the automobile using the National Old Trails Road, later known as Route 66.

Coming of the Railroad

With the coming of the railroad in the 1880s, and the interest in mining around the same time, Caucasians began living in the area around Newberry Springs in the 1880s and 90s. Because of the boom-to-bust cycle of mining, people would live in an area for a year or so, then move on to the next mining boom, leaving that area with their buildings abandoned, although some of those buildings were moved to the next boomtown.

However, small communities that supported the railroad lived on until the 1960s as trains needed to be serviced every so often (50 to 100 miles). That servicing mainly consisted of topping off steam locomotives with water. When train locomotives switched from steam to diesel power around 1940s and 50s, those services were no longer required and many of these communities slowly disappeared.

Located at most of those support communities, the railroad built what were called “section houses” next to the tracks. This was the base of operations for managing and maintaining a particular section of railroad track. Section houses housed the on-duty telegrapher, it served as living quarters for the railroad workers assigned to this section, and was used for storing maintenance equipment. Unfortunately, most of these section houses that used to exist in such communities were torn down, including Newberry’s.

According to Bill Smith, many of the railroad workers living and working at the Newberry section house were either Navajos or Pueblo people (e.g., Hopi, Zuni, etc.) that the Santa Fe Railroad recruited from Arizona and New Mexico. These people were hard workers and very skilled at maintaining the railroad. Often, when the workers needed to travel out to a place along the tracks that needed attention, they would use classic railroad handcars for transportation.

When the railroad was first built in 1880, the abundant water supply in Newberry was realized. The town’s name supposedly came from two brothers, named Newberry, that lived near a large spring. This would later become known as Newberry Spring, which is now currently dry. In 1919, the railroad renamed the town to Water, as it was a primary water source for their steam locomotives. Water was shipped from here to other places east that had little water, such as Ludlow, which was a railroad junction town until 1941 and needed a lot of water.

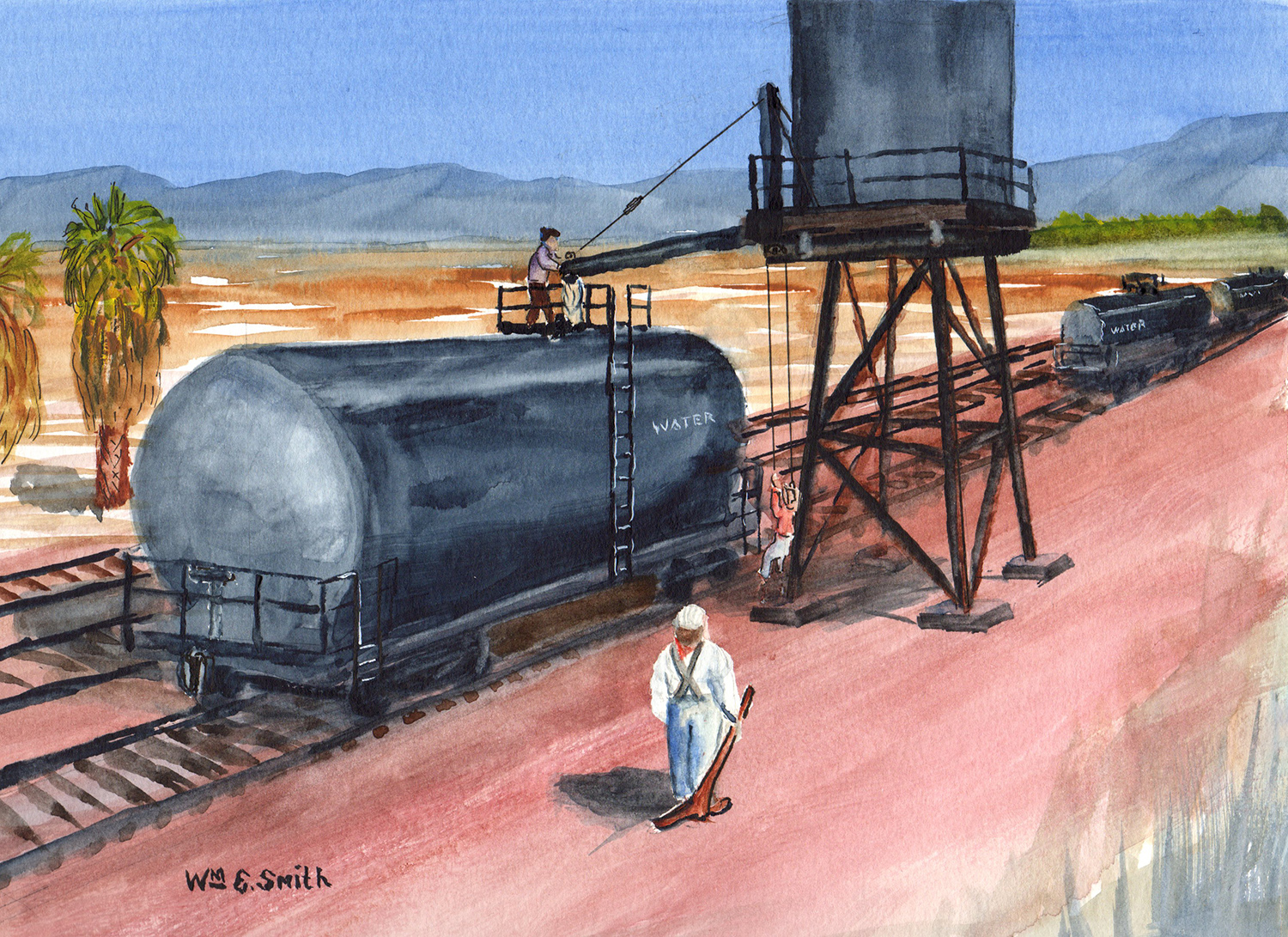

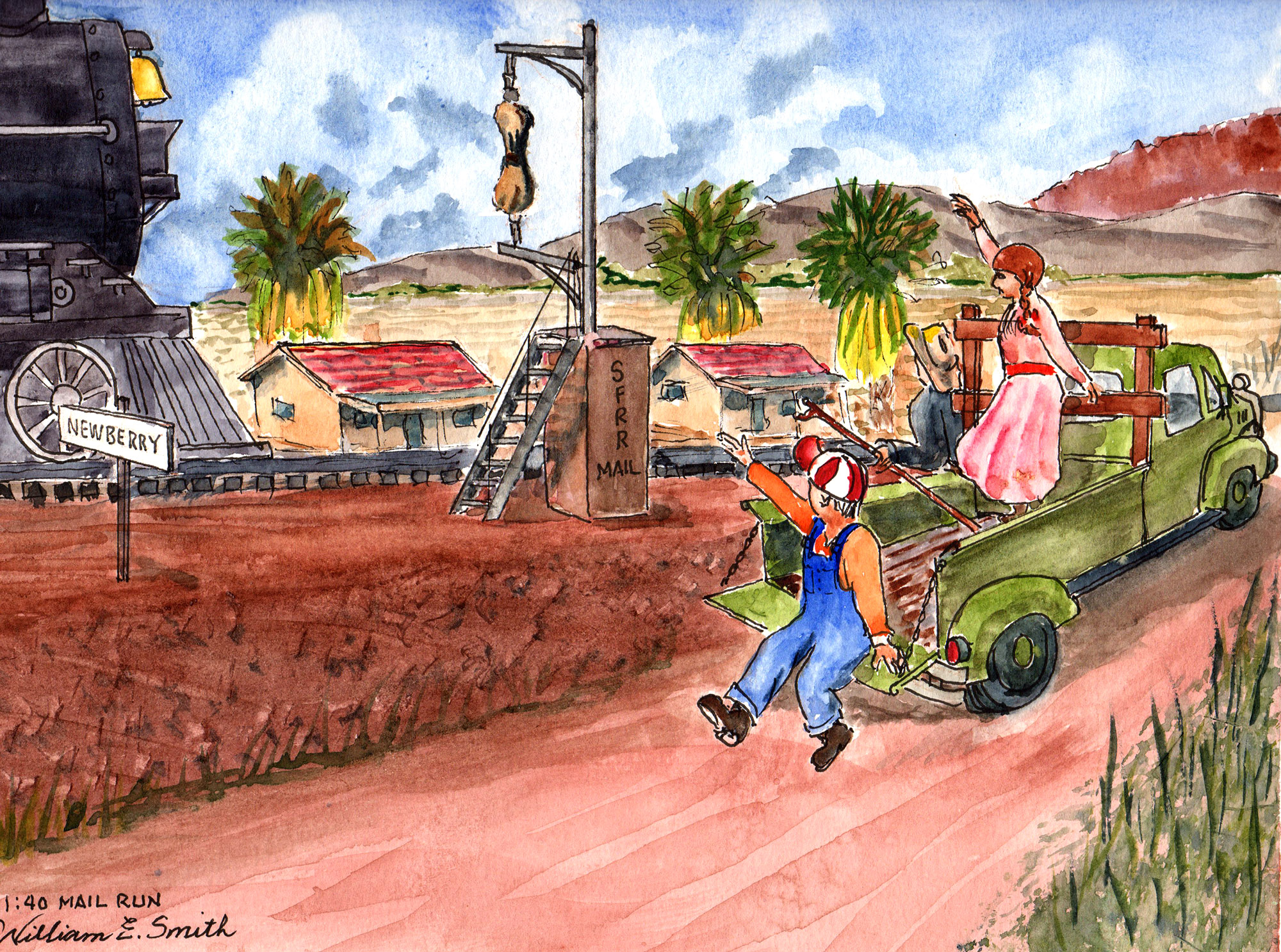

The above painting by Bill Smith depicts a scene of a water tank being filled with water from Newberry that will later go to points east, most likely Ludlow, to be used in steam engines. This tank was later replaced with a much larger tank. This tank was removed after the 1992 Landers earthquake (magnitude 7.3) when it cracked, leaked a lot of water, and caused a flood.

Below are pictures of a similar tank that was used by the railroad that can still be seen along I-40 on the California-Arizona border, where there was another ample supply of water, on the east side of I-40’s bridge over the Colorado River. Also below are pictures of where the section house and water tank once existed. This scene is looking to the east where Mountain View Avenue crosses the railroad tracks. Notice that the palm trees depicted in Smith’s painting still exists today.

Incidentally, the town’s name of Water was changed back to Newberry around 1930. Later, in 1967, the name was changed to Newberry Springs, thanks to a unique individual named Mrs. Orcutt that was living here at the time and was later famous for creating the World’s Longest Driveway.

National Old Trails Road & Route 66

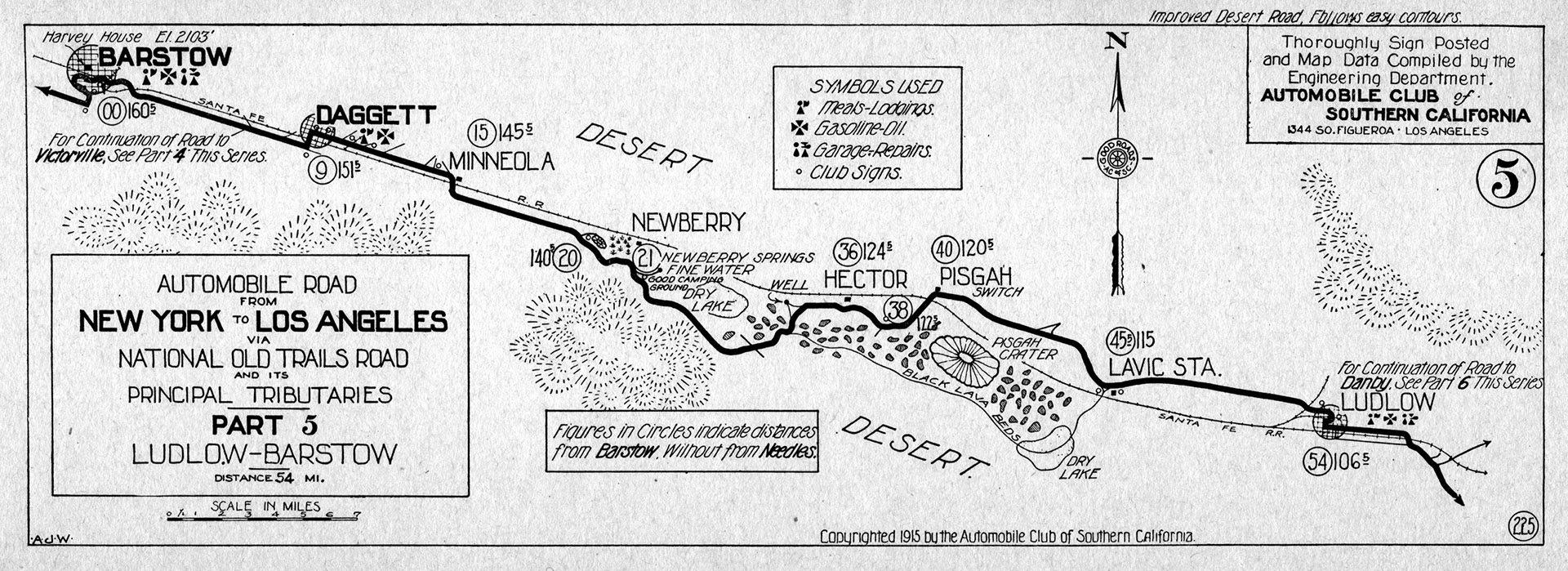

With the dawn of the automobile in the early 1900s, there was a need to create several “ocean to ocean” roads. One of those was called the National Old Trails Road. It was established in 1912 that began in Baltimore, Maryland, and stretched to Los Angeles, with branches going to San Francisco and New York.

An enterprising blacksmith in Daggett named Seymour Alf was awarded the contract to grade the road from Barstow to the California/Arizona border. Alf began grading the road with a horse-drawn grader. Learn more about Alf’s operation in the Daggett article.

The western half of the road, consisting of both mountainous and desert terrain, was mostly dirt and difficult to drive. By the mid-1920s, the road was difficult to maintain and ran the risk of being decommissioned (ending Federal funding).

Luckily, in 1926, thanks to the new U.S. designated highway system, a highway numbered 66 was commissioned to run between Chicago and Los Angeles. It would use the existing National Old Trails Road alignment from roughly Las Vegas, New Mexico to Los Angeles. This would be the beginning of a big economic boom for towns along this segment of road, including Newberry.

Homesteading

The Homesteading Act included the Mojave Desert starting around 1910. This brought interest in the land around Newberry Springs in the 1920s, and even more so ten years later during the Great Depression. A new breed of settlers laid down roots in what is now Newberry Springs, with its abundance in water, free land, and easy access to transportation with Route 66 and the railroad. Many people quickly learned how to live in the desert, which was quite different from where they came from.

Settlers quickly learned how to farm their free land. With the abundant water supply of Newberry Springs, growing vegetables was fairly easy. Incidentally, land that was homesteaded needs to be visibly worked for three years in order for ownership to be granted to the settler. The settlers-turned-farmers quickly discovered that the ancient lakebeds they were farming on consisted of alternating layers of clay and sand. Some soils worked great for farming, while others didn’t. However, the other soils, such as clay, were used for making adobe bricks and mortar for construction material, as well as for lining water reservoirs.

The vast desert landscape and remoteness of Newberry Springs gave the settlers the same challenges that settlers faced in places like Nebraska and Kansas – they were living in a remote area, far from any settlement with supplies. The settlers that stayed with it for those three years to own the land had to be a though bunch. They had to survive without the conveniences that they once took for granted in their previous home. They had to be tough, but also independent, and self-reliant. And, they had to be able to not only tolerate the loneliness of the remote desert, they had to love it. In Newberry Springs today, you still see many of these same traits of the citizens that live there now.

The period of time when settlers were arriving and setting up their homesteaded lands coincided with an unusually wet climate cycle. This was roughly in the 1920s and 30s. The wet climate at the time seemed normal to the newly arriving settlers. However, towards the end of the 1930s, this cycle ended, and the desert returned to its normal drier condition. Along with this and other conditions, many settlers abandoned their homesteads and either returned to where they came from or moved further west towards the California coastal regions.

Between 1920 and 1933, prohibition in the United States was in full swing. Relying on the remoteness of Newberry Springs, settlers began bootlegging operations. It was nothing compared to the bootleggers elsewhere in the Nation, but it was another way the settlers could carve out some income. Since Newberry Springs was far from any market, transporting the moonshine many miles away to a population center posed a challenge. By the mid-1930s, stills evaporated around Newberry Springs.

Living Conditions in the Desert

People living in Newberry Springs, whether they were the initial settlers or people that later became permanent residents, learned how to adapt to desert living. The top priority was access to reliable water and being able to produce food.

The Home

In the 1920s, available building supplies were non-existent. There was no Home Depot or hardware store within hundreds of miles. There were also no building contractors. If you wanted to build a home, you had to do it yourself or by someone experienced in building homes that lived nearby, using whatever materials you could get your hands on.

The walls of buildings were often made from the adobe blocks built nearby as explained under Homesteading. Walls and roofs were also constructed of wood. Chicken wire and plaster were usually available, so they filled in other ways of creating a barrier or divider.

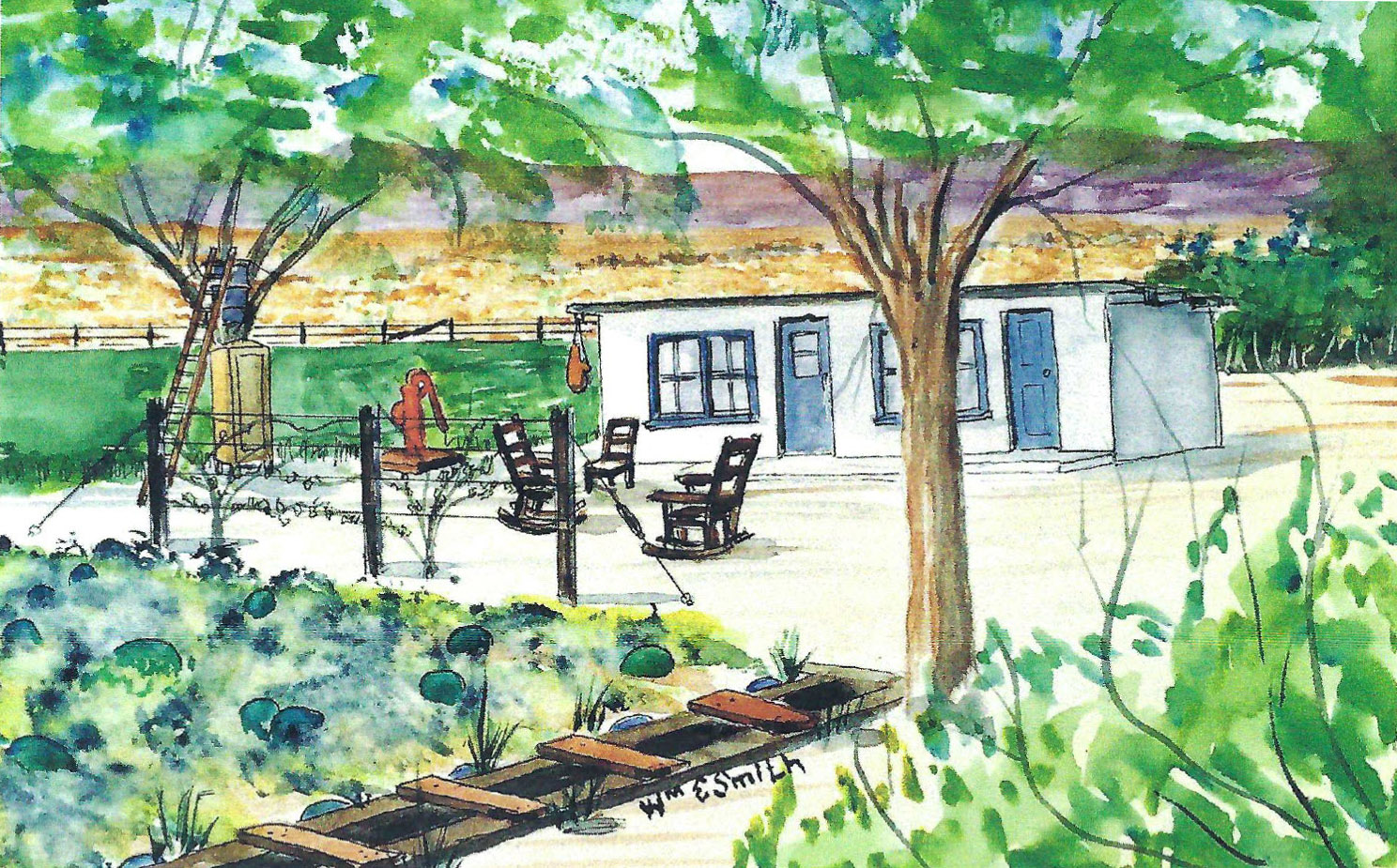

Planning where to build your home on your property was important. Naturally, placing it under the shade of a tree, providing one was available, for cooling was critical. If a tree wasn’t available, several fast-growing ones, like cottonwood trees, were planted. The location of a water well was also a consideration. Some wells only produced water that can be used for washing and other uses, where other wells, ones that were typically deeper, had water that could safely be used for human consumption.

Providing there were enough shade trees, and given that many dwellings were rather small, a lot of time would be spent outdoors. This made for planning a living space, like a family room, outdoors and near the dwelling. It was common to have a permanent table and chairs that wouldn’t be blown away in the wind just outside the dwelling and taking advantage of shade trees.

Growing Food

Producing food often meant growing it yourself. Successful residents dedicated several acres of land to cultivating big gardens and/or fields of hay for livestock. Wild burros, jackrabbits, quail, and homegrown chickens filled in other protein needs. Vegetables from gardens grew nicely. Some residents experienced bumper crops of different vegetables, which created a lot of commerce between neighbors using the barter system. Perishable items were either immediately consumed, dried, canned or shared with family and neighbors.

By the mid-1930s and into the 1940s, more commerce came to the area around Newberry Springs, consisting of more mining and the military bases, mainly the Douglas Aircraft facility that was built between Newberry Springs and Daggett. Some enterprising residents that grew bumper crops that grew well in the desert, such as watermelons and cantaloupe, took boxloads of them to such places. They were placed in areas where all the employees can access them, along with an empty coffee can. At the end of a workday, many of the melons would be gone and the can was full of money. Back then, people openly used the “honor system” to pay other people for their goods.

Keeping Perishables Cold

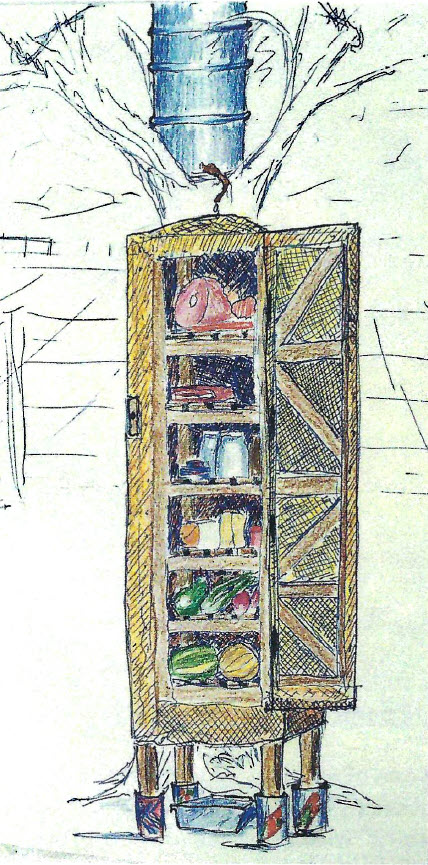

Even with the practice of consuming or trading perishable food items as quickly as possible, it was still necessary to keep them available for a few days when preparing your own meals. Enter the desert cooler.

Many desert dwellers built their own desert cooler using a somewhat similar design. Using the cooling processes of evaporation and the ever-present desert winds, it kept items such as smoked meats, cheese, butter, eggs and vegetables cool and in good shape. Water would soak burlap material that covered a wooden framework of shelves that would resemble a modern-day refrigerator.

The desert cooler was then placed directly under a tree for both shade and utilizing its branches to support and hold a tank of water. The tank would constantly feed the burlap with water so that it was always soaked, meaning that someone had to constantly climb up the tree with buckets of water to keep the tank full. Along with the shade produced by the tree, the wind would blow through the burlap creating an evaporative cooling effect. Amazingly, the desert cooler would keep butter so cold, you couldn’t spread it on fresh bread.

Water would continually seep down through the burlap that covered the box portion and would eventually drip down the legs of the desert cooler. Those four legs were placed in individual tin cans that filled up with the water running off the burlap, which kept ants from getting into the food. There was also a shallow pan kept under the desert cooler that water dripped into so that the dogs and cats could have a cool drink of water when they needed to.

Modern Conveniences

Electricity wasn’t generally available to Newberry Spring residents until the 1940s. Property that was close to Route 66 or Newberry Road was able to tie into electricity first. Later, power lines were strung to outlaying areas. By the 1960s, most properties were hooked up to power.

By this time, more supplies were available in Barstow, which was only 22 miles away. One of those commodities was ice. It was common for Newberry Springs residents that didn’t employ a desert cooler, discussed earlier, to make frequent trips to Barstow to purchase ice for their iceboxes to keep perishables cool. Building supplies were also more readily available in Barstow. Many children were sent to Barstow daily to attend middle and high school.

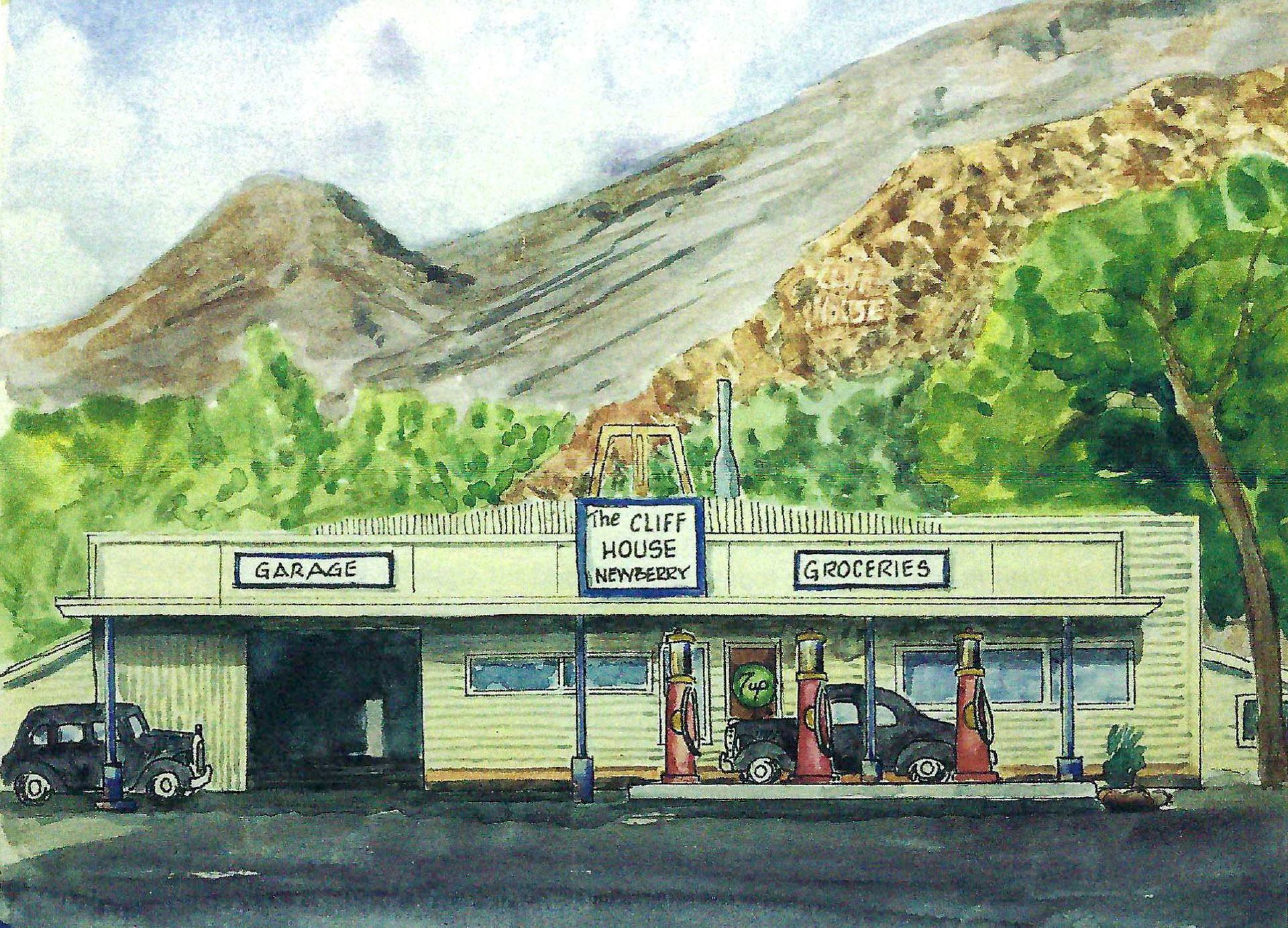

Businesses also began to spring up in Newberry Springs along Route 66. One of the more prominent and important businesses was The Cliff House. It was established in 1929. See the Newberry Springs Driving Tour for driving directions. The Cliff House had something for everyone.

It was a full full-service desert oasis that included a garage, store, café, cabins, post office, general store, and even a swimming pool. Gasoline was for sale and dispensed using gas pumps where the fuel was hand pumped into a glass container at the top of the pump, then gravity fed into an automobile’s gas tank. With Route 66 being open for just three years when The Cliff House opened, the garage, café, and cabins were a welcome site to the weary traveler coming from Needles.

The swimming pool was famous, as its clear, cool water was advertised on signs along the road from Needles to Newberry Springs. Local children were able to swim in the pool by paying 10 cents and, in later years, 25 cents. The large cottonwood trees that once grew all around the property were watered every Friday night when the pool water was let out to flood the whole property. Saturday morning, local children would show up to clean the pool in lieu of paying the pool’s entrance fee. The pool would be filled up with the property’s ample water supply in a short period of time.

Later, towards the 1960s, The Cliff House became more of a hardware and general store for Newberry Springs. It was renamed to Deel’s, reflecting the new owner’s name. It remained open until the mid-2010s.

Communication

Between 1880 and 1930, communication to and from places outside of Newberry was either done by telegrapher from the section house described earlier under Coming of the Railroad, or simply by word of mouth by people traveling on the road. The railroad’s telegrapher could only be used for railroad business and rarely used by citizens of Newberry.

One of the primary methods of communication during these times was through the U.S. Mail, which arrived and departed via passing trains. This process was done in a traditional manner where a mail car on a moving passenger train would simultaneously drop off a sack of arriving mail onto a platform and “snag” (catch) a sack of outgoing mail hanging from a post. The platform and post were located near the section house mentioned earlier. There were several railroad sidings near the section house, which required the trains to pass through multiple track switches. This meant the trains had to slow down to around 30 miles per hour (48 kph), making it safer to drop and pickup the sacks of mail.

The following painting by Bill Smith depicts an approaching train just before snagging a mail sack from a post. This activity occurred near the section house explained in Coming of the Railroad above.

Trains mostly kept to a strict timetable, one that many people would set their clocks to. The only method of communication was the telegrapher in the section house. There was no radio or telephone available were train crews or section houses could communicate with each other. Railroad gangs from the Newberry section house that maintained tracks, needed to know exactly when they could expect a train on their section of track. Plus, the crews operating the trains needed to know when other trains would be at different places. For that reason, everyone lived by the schedule and timetables of when trains were expected, making it necessary to have an accurate clock or watch.

Communication & The Cliff House

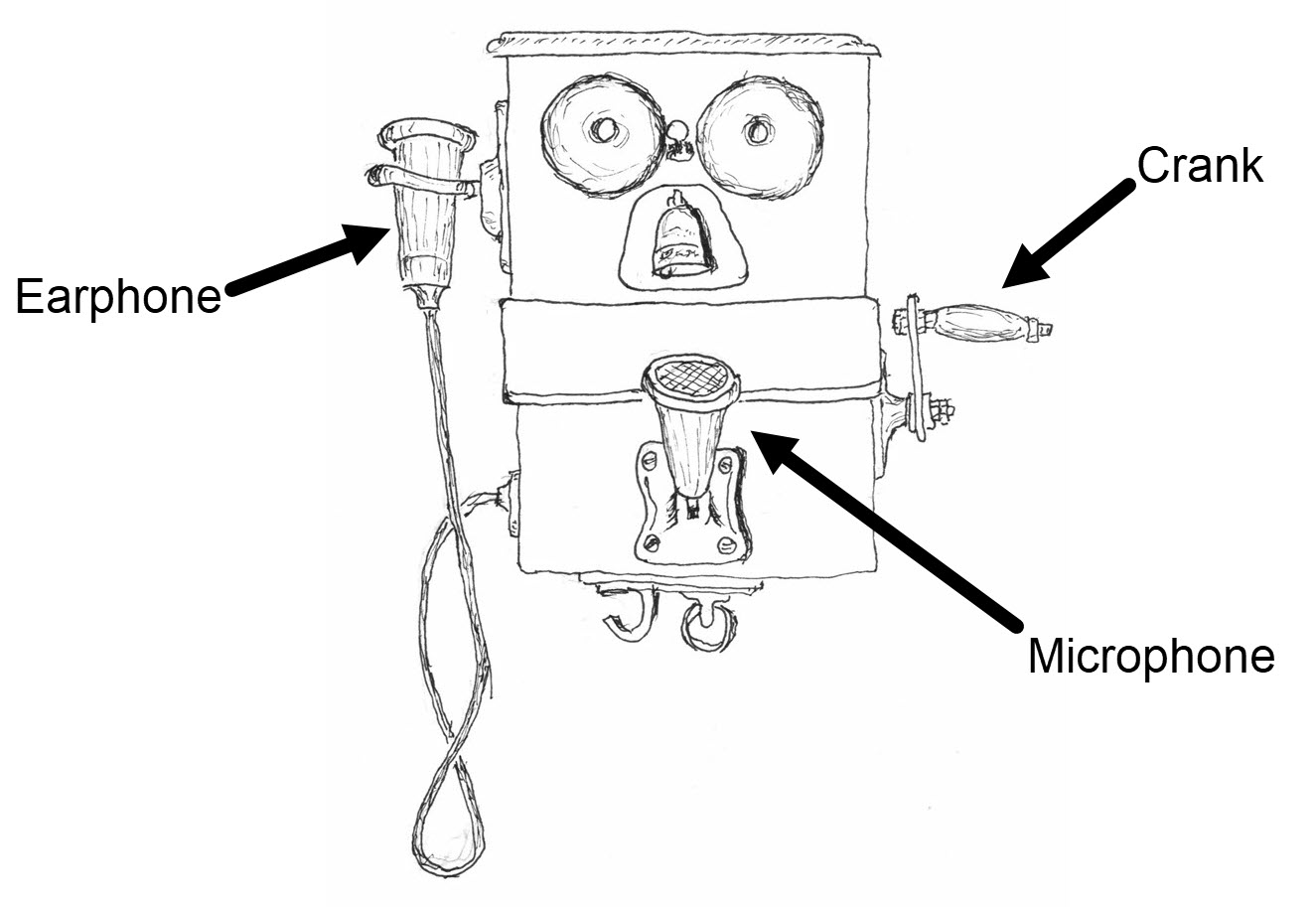

The aforementioned Cliff House was also the hub for communication and transportation. It had the only telephone in town. Beginning in the 1930s, The Cliff House had a classic wooden-crank phone hanging on one of its walls. It was connected to a “party line”, meaning that several parties, in this case, several towns, talked on the same line. You could only use the line when nobody else was using it.

In The Cliff House, people constantly listened for incoming calls based off the series of rings. When a long ring, followed by a short ring, was heard, it was a call for someone in Newberry Springs. If there were two short rings, the call was for Daggett, and if it was two long rings, it was for Ludlow. Naturally, if someone was calling for a resident somewhere in Newberry Springs, workers at The Cliff House would take a message, get it to the resident, so that they could get to The Cliff House and call the party back.

Outgoing calls were a different process. To begin, you would pick up the microphone (attached to a wire) hanging on the phone’s left side, then crank the leaver on the phone’s right side. You would give the leaver one long crank, about three seconds, then one short crank, about one second. Then, you would hold the speaker to your ear and wait to listen for the operator to begin speaking. The operator would ask for the number you wished to call and, if the line was available, put the call through. If the circuits (lines) were busy being used or the party you were calling was not available, the operator would continue to try until a connection was made, then call you back to connect you to your party. After making a call, the operator would tell you the charges and you would go to the cashier at The Cliff House to pay them. For many rural communities across the USA, this was the typical way of using the telephone.

Personal telephones in private residences didn’t arrive in Newberry Springs until around 1959, eliminating the need for everyone to go to The Cliff House to use the phone.

Transportation

Along with driving an automobile on Route 66 to various places, there were other forms of transportation, such as bus service and trains. Newberry Springs was serviced by both Greyhound and Continental Trailways bus lines. Before there was bus service, the Santa Fe Railroad also offered a “whistle stop” for train service at a place near the section house described above under Coming of the Railroad.

For various reasons, people had to get to Los Angeles, which was 165 miles away. The closer town of Barstow didn’t have the services L.A. had in the early years. That meant a drive that took 10 to 12 hours. It took this long because of poor road conditions, especially over the Cajon Pass, plus automobiles went slower and required more time to “rest”, such as stopping to either let the radiator cool down on hills or to fill it up with water to prevent “boil overs”. Flat times were also very common, so time was spent changing tires during such long trips to L.A.

In Newberry, there were both “highway” and “non-highway” people. Highway people were people that lived by and made their living off of people that traveled along Route 66. These people had hotels, cafés and garages. Mechanics in these garages were known to charge higher-than-normal prices to people traveling the highway since there was nowhere else to go. Non-high people were mainly farmers and people that made their living from the agriculture business that thrived in Newberry. Highway and non-highway people did not mingle with each other socially.

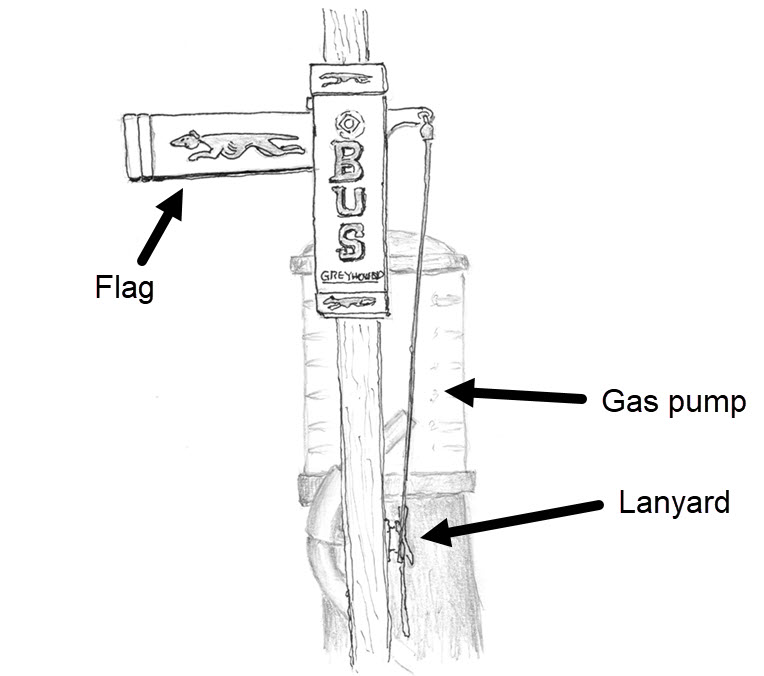

Both Greyhound and Continental Trailways bus lines stopped at The Cliff House, adding to the reasons why this was the center point of Newberry Springs. From the 1930s to 1960s, there were sometimes four Greyhounds and two Continental Trailways buses passing at The Cliff House over a 24-hour period.

You had to have some knowledge of how to use either bus line. For one, you had to be familiar with the bus schedules. The latest ones were posted on a wall in The Cliff House. Second, you had to know how to use the flag system. A flag box, one colored grey for Greyhound and another red for Continental Trailways, was located on poles next to the gas pumps of The Cliff House. For the bus line of your choice, you would pull a lanyard that would raise a painted and appropriately colored rigid flag for the bus driver to see. These flags were similar to the old traffic signals used in the 1920s and 30s.

When the bus arrived, before you boarded, you were responsible for using the lanyard again to drop the flag back down. The bus would not leave with a flag still up. The buses all had spotlights that were used to look for flags as they passed The Cliff House at night.

The first eastbound Greyhound bus in the morning dropped off the newspapers. It also dropped off any urgent items that were ordered from the Cliff House the day before, such as parts for a stranded motorist’s automobile. This service was similar to overnight shipping available from companies like Fedex.

Water and the Mojave River

Many properties you see today in Newberry Springs included irrigation reservoirs that were leftovers of the times when the original pioneers created such ponds to store water for longtime reserves. By the 1950s, due to the seemingly endless supply of easily accessible water near the surface throughout Newberry Springs, many landowners began using these ponds for purposes other than just storing water.

One of these purposes was for starting fish farms. In the 1950s, many people found income by cultivating catfish, which were easy to raise. One person, that being Bill Smith, began a co-op service, like those used in farming areas like the San Joaquin Valley of California. Mr. Smith would establish places or clients to sell the fish, such as lakes in need of restocking managed by different counties in Southern California. Property owners that raised catfish would sell their fish to Mr. Smith, who in turn delivered larger quantities to these clients. It was a win-win situation for all parties.

One fish farm still exists as of 2025 and has been in business since the 1980s. It raises coy fish (not catfish) that are sold to fish dealers and landscapers for decorative ponds all over the United States. The farm’s owner has entered their colorful fish into competitions and has won various awards.

Starting in the late 1950s, a waterski lake was built by Dr. Horton that became Horton’s Waterski school and became internationally known. Shortly afterwards, other people began building lakes for waterskiing and recreation. These lakes were considerably larger than the earlier fish ponds. Lakes were built in a north-south orientation because the wind mainly came from the west reducing wind-generated waves.

Larger properties were combined into a multi-property communities, similar to a homeowners’ association, that shares a lake. Most of these lakes are less than a half mile long and are oval-shaped so that the boat pulling the skier can continue going for multiple laps. There are about ten of these communities scattered around Newberry Springs. The largest one has a 50-acre lake with about 30-40 residences. This is the largest in the area. Another lake is well-known in the waterskiing community and has big-name waterskiing competitions on a regular basis.

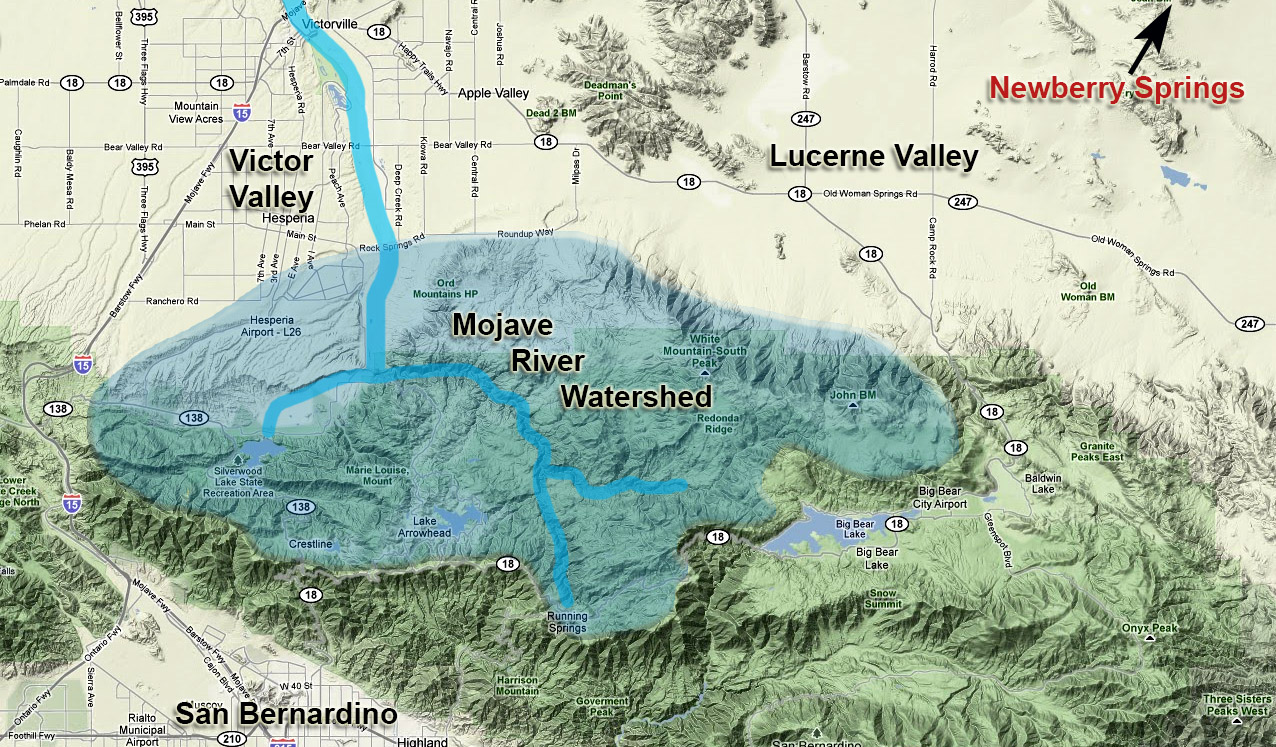

By the 1980s, the desert area was becoming more populated. Not only were more people moving into Newberry Springs and building more homes, but there was a much larger increase in homebuilding taking place further up the Mojave River, mainly in the Victor Valley (i.e., Apple Valley, Hesperia, and Victorville).

The headwaters of the Mojave River are in the San Bernardino Mountains, roughly 80 miles (128 km) up-river from Newberry Springs. It ends in a dry lake near the town of Baker along I-15. The Mojave River is very unconventional when compared to other rivers. It flows away from the ocean and never empties into another river or the ocean. Often, the Mojave River has no surface water as much of its water flows underground. The surface of the riverbed is mostly sand.

All the communities up-river took water from the Mojave River. As demand increased in the Victor Valley due to increased population, less water flowed through to Barstow and Newberry Springs. By 1990, the water levels in the Mojave River became alarmingly low. The City of Barstow took action and filed a lawsuit against every well owner in the Victor Valley, of which there were over 200 of them, including the water districts that owned them.

In the meantime, various droughts also occurred, reducing the amount of water that normally flowed in the Mojave River. Along with the lack of water, this also meant dryer conditions. Many newer residences in Newberry Springs that were built near the Mojave River saw an increase in drifting sand because of the dryer conditions. Often, these sand drifts would overwhelm and bury some residences during windstorms.

Some residents filed a lawsuit against the County of San Bernardino for miss-management of the river, since it was under their purview. Years later, some property owners received a settlement from the County and their abandoned homes still can be seen in Newberry Springs today. All that remains of some of those homes today is their chimney or roof sticking out of the sand dunes – the actual homes buried in the sand below.

The Barstow lawsuit was complicated as it had to be negotiated with a lot of well-owners. A settlement was reached where water from the California Aqueduct, also known as the California State Water Project, that passes through the town of Hesperia and near the Mojave River, was purchased and sent past the Victor Valley to communities down-river via a pipeline.

In the late 1960s, the Mojave Water Agency (MWA) was established as part of the California Aqueduct. It was one of 29 water agencies that were established to wholesale and distribute water from the aqueduct. The MWA covered the area of the Mojave Desert, roughly from the Victor Valley, east to Yucca Valley, north to Barstow and Newberry Springs, and west to the Los Angeles County border.

In the 1970s, there was no need to distribute water to any of these regions until the 1980s, when the communities around Yucca Valley (50 miles southeast of Newberry Springs) had to impose a home building moratorium for lack of water, as they were also experiencing a population explosion. These communities entered into an agreement with the MWA to build a pipeline aqueduct from Hesperia to groundwater discharge basins in Yucca Valley. They would then purchase water regularly from the California Aqueduct through the MWA.

By the mid-1990s, the Barstow lawsuit was finally settled (adjudicated) by having the MWA regulate the traditional amount of waterflow down the Mojave River past the Victor Valley. The extra water that communities in the Victor Valley needed, were purchased from the MWA which came from the California Aqueduct. The MWA became the court-appointed “water master” that became responsible for monitoring water usage from all the wells so that all parties were rightfully charged for the water they consumed. Down-river communities, like Barstow and Newberry Springs, also had constraints put in place, monitored by the MWA water master, where they could only consume water at levels that existed around 1990.

The MWA also built another pipeline aqueduct from the California Aqueduct in Hesperia to various discharge points in Barstow and Dagget that would replenish the Mojave River with water. This water from the aqueduct returned normal waterflow to the river and the problem was solved.

During the negotiation process of the lawsuit, a ruling was also made to not create any new ponds or small lakes in any desert community, including Newberry Springs. Any existing pond was “grandfathered” in. Already in the 1970s and 80s, some property owners stopped caring for their ponds and they dried up. After the lawsuit, those property owners were no longer able to restore the pond to its previous state. For that reason, there are less ponds in Newberry Springs today than there were in the 1970s.

The Existing Buildings of Newberry Springs

The following will provide a synopsis of the historical buildings and sites one will see when they drive east on Route 66, between the Newberry Springs and Ford Cady Road exits on I-40.

Highway Maintenance Yard

Driving from west to east, the first historical set of buildings on the right side about one quarter mile from I-40 is the original highway maintenance yard built in the 1920s, when the roadbed for Route 66 was being built. There are a few buildings left where the maintenance workers lived. As of 2022, the property is privately owned and fenced off.

Deel’s

The next building on the right after the maintenance yard is the former Cliff House discussed earlier, now known as Deel’s. The last time the building was open, it was a hardware and general store. We last saw it open around 2012. As of 2025, the owners still live in Newberry Springs and the old Cliff House may see life again someday.

The Barn

Across the street from The Cliff House and a little to the east is what we know now as The Barn. This site too has a storied past. Starting in 1951, a couple with their high-school aged daughter bought the property and built a brand-new market and café with living quarters in the rear. It had Union 76 gas pumps out front. The building was nicely built with stained wood siding and a blue concrete-tile roof. The inside was all knotty pine walls with recessed lighting in the ceilings. It had modern refrigeration and air conditioning – top notch hardware all the way. Sadly, it was open for only a short time when the father died of a heart attack. The wife and daughter couldn’t run the place, so they sold it to new owners that ran the store until 1955. Several owners and ten years later, when I-40 was being built, the building mysteriously burned to the ground.

The original “Barn Bar” (as it was called then) was located on Mountain View Road near the railroad tracks. The building was actually a real barn from a ranch, which is how it got its name, then moved to this site in the mid-1950s and converted to a tavern. It hosted many community parties and fund raisers. Most of the events, such as the Newberry Follies Can-Can Show and dances, raised money for building the Newberry Community Building that is now located on Newberry Road, half mile south of Route 66. This original Barn closed after I-40 was built. The Community Building was built in 1957 and funded solely from those fund raisers and volunteer builders.

The Barn that we see today was built on top of the foundation of the market that was built in 1951 and later burned down. Today, The Barn is a successful and popular establishment that attracts travelers along Route 66 as well as motorcycle clubs that venture up from Los Angeles for weekend outings. The Barn hosts many events including a monthly swap meet. See the Newberry Springs Chamber website for details.

Newberry Spring

A short distance past The Barn, the road passes by a small hill on the left. Just past the hill is the site of Newberry Spring. Along with Troy Lake, which is a few miles to the east, Newberry Spring always had an ample supply of water for the first travelers along the old road that really needed it.

Newberry Spring was a place where a lot of highway travelers would camp overnight to take advantage of the numerous shade trees and supply of water. This was back in the day when there were very few hotels along Route 66. As you’ll see when you drive by here, that doesn’t exist today. The spring’s waterflow began decreasing significantly in the 1940s and by the 1950s was completely dry. This became true with several other springs in the area.

During the 1940s and 50s, traveling merchants, known to everyone as Gypsies, came here to Newberry Spring in horse drawn wagons. They would setup camp the night before and started a big campfire to attract people from all around. The next day, people from all around Newberry would arrive at Newberry Spring to sell and trade goods with the Gypsies.

They were known to make their stop at Newberry Spring a few times a year. This activity continued past the 1950s, but they no longer arrived in horse-drawn wagons but with campers and trailers instead. As the spring dried up after around 1960, they no longer came around.

Here’s a painting by Bill Smith of one such Gypsy trading event at Newberry Spring in the early 1940s:

Swampy Area & Troy Lake

Continuing east past Newberry Spring for the next 3-4 miles, Route 66 sits on a raised roadbed for a reason. When National Old Trails Road was built around 1915, due to the springs, this area was always a marshy area throughout the year with lots of cattails, desert willows and cottonwood trees. Additionally, after rainy periods, water would flow out of the mountains in the south and fill up these lowlands, as well as Troy Lake that is situated 5-7 miles east of Newberry Spring.

Given that this swampy area was filled with water throughout the year, National Old Trails Road was routed around it and Troy Lake to the south (see Newberry Springs Driving Tour), which was on higher ground, nearer to the mountains. Even when there was lots of water, it was rarely 2-3 feet deep. When Route 66 was built in 1926, it was routed as a straight line with the railroad tracks (which was already on a raised bed) and laid down on top of a raised roadbed to be out of the water.

That raised roadbed also acted as a levy. Water that flowed down from the mountains, often as flashfloods during the summer monsoon season, would be contained to the south side of Route 66. That’s why, when you drive on the road from west to east, most of the businesses and buildings are on the left (I-40) side of the road.

Troy Lake was not associated with the swampy area near Newberry Spring. It is a low spot where standing water accumulates. Whenever there was water in Troy Lake, it was because of storm runoff from the various mountains. Like many desert basins, Troy Lake is a low spot where water flows. Since rainstorms aren’t intense every year, during dryer years, this area is referred to as Troy Dry Lake because it doesn’t contain water.

For various reasons, mainly because of increased consumption of water from the Mojave River aquifer, as well as an increasingly drying climate for the past 40 years, Troy Lake and the swampy areas are dry most of the time. The term Troy Dry Lake is a more frequently used term. Only during very wet seasons does water reappear in the old swamp area, but nothing like it was before 1950.

Bagdad Café

Two miles from Newberry Spring, Bagdad Café will be passed on the left. This is now a well-known attraction for Route 66 roadies and enthusiasts. The café was built in the 1950s and originally called the Sidewinder Café. It also included a cinder block hotel that was built around the same time. The hotel and its big classic sign were two more historic features along Route 66. Unfortunately, the hotel was torn down in 2015. Fortunately, however, the sign remains.

Both buildings gained fame with the filming of the 1987 movie of the same name, The Bagdad Café. After the movie, Bagdad Café became an attraction, and the new owners renamed Sidewinder Café to Bagdad Café. Bagdad Café shouldn’t be confused with the Route 66 town, also called Bagdad, located 50 miles east of Newberry Springs.

Learn more about Bagdad Café on the Route 66 Barstow to Ludlow road trip article.

Two Gas Stations

Not far past Bagdad Café, the ruins of a Whiting Bros. Gas Station will be seen. It can be identified with three gas pumps (if they’re still standing) sheltered by an overhang with a yellow stripe. Sadly, this site has been deteriorating rather rapidly over the past ten years. Regardless of its condition, this site has some fun history.

This property began prospering in the 1950s. If you look closely at the wall nearest the gas pumps, you’ll faintly see the words “Tony’s” and “Italian”. That’s because, this was once Tony’s Spaghetti House.

According to Bill Smith, Tony was a real character. Nobody knows what drove Tony to build an Italian restaurant in the middle of the desert! Tony tried real hard to make a go of the restaurant and was always friendly when you came in. The food wasn’t that bad for such a remote place. By the late 1950s, Tony sold out and the property became a Whiting Bros. gas station.

After I-40 was built in the late 1960s, both Whiting Bros. gas stations business dwindled and eventually closed.

Behind Tony’s were several small buildings which are still visible today. The buildings always seemed to have young women in them. It seemed there was a turnover of women living in these buildings as it was related to the hitchhiker population at the time. What became more obvious was the increase of trucks parked for a long period of time near the gas station. They were not there just filling up on fuel. It soon became known that Tony was running a house of ill repute! The local teenagers were known to blackmail Tony to sell them beer, otherwise they would turn him in to the authorities for prostitution. So, Tony did sell them the beer they wanted, just at double the price!

Just past Tony’s was Reed’s Texico Station. This building still exists in 2025 and is in great shape. Mrs. Reed and her son Bobby ran the place for quite some time around the same time Tony’s was in business. It was always spic and span and well maintained. Today’s owner still holds that tradition. Reed’s always had the coldest soft drinks in Newberry. You could pull a Coke or Nesbitt Big Orange Soda out of the cooler, and when you opened it, all the liquid in the neck of the bottle would freeze when it was opened.

Fort Cady Road

There were several buildings and businesses between Reed’s and the intersection of Route 66 and Fort Cady Road. Most are either small ruins or completely gone. These buildings included Dutch’s Garage, another hotel, and another Whiting Bros. gas station. For a period of time, Newberry had two Whiting Bros. stations open at the same time.